What they don't teach you in Entrepreneurship Class

- Adrien Book

- Nov 1, 2018

- 5 min read

Updated: Dec 31, 2022

Finding success in entrepreneurship is hard. I would know. I have spent many years talking about, or being involved in, entrepreneurship. I started a UK-based fashion business six years ago, and that all-encompassing dumpster fire makes up most of what I know today about marketing, e-commerce, branding, and how no one will buy your stuff if you just do things the way they’ve always been done.

Four years later, I got back onto the anthropomorphic entrepreneurship horse and tried to start a German-based social business, which had the goal of providing affordable and safe housing to German sex workers. That too was a failure. Turns out it’s hard to get people to care about people who have sex for living.

In addition to these half-baked experiments, I followed a handful of entrepreneurship classes at the University of Exeter (England), Universität Mannheim (Germany), and ESSEC Business School (France). Beyond what I’d learned practically, these courses gave me what I’d call a blanket theoretical knowledge of what it takes to call oneself an entrepreneur (big surprise, I don’t have what it takes).

I only describe this to highlight the fact that the following few paragraphs are the result of careful consideration. It’s not that I’m anti-innovation or a disbeliever in disruption (or whatever another aggravating cliché the start-up community may use), or even a regulation hawk (but companies should be held accountable for the harm they may cause, sue me) : I simply think that entrepreneurship is rotten to its very core and that one way to fix it is to change some of the things we teach about it in business schools.

It wasn’t always this way. Things were going pretty smoothly on the good start-up ship ten years ago, but ever since the captain/government gave the keys to the passengers/founders, there are people passed out everywhere, rowdy guests are throwing empty beer cans at the neighbor’s garden and the furniture is getting trashed. Things got so out of hand that the cops won’t even show up because half the guest have enough money to make anyone’s and everyone’s life a living, dystopian nightmare (looking at you, Facebook, Amazon, Google…).

Fun metaphor aside, I believe three things should be explained to young ones to prepare them for modern entrepreneurship: Safety Nets, Shortcuts and The Five.

Safety Nets

Students in virtually every higher education classroom throughout the world are told that they can make it as an entrepreneur with only a great team and an astounding idea (hell, for some courses, the entire curriculum revolves around that idea). That’s, however, turning a blind eye to the most common shared trait among entrepreneurs: access to financial capital (family money, inheritance, or connections that allow for access to financial stability).

It’s easier to create Snapchat if you live near Eric Schmidt, both your parents are lawyers and you can afford to have internships in South Africa.

Kids are being seduced into thinking that they can just go out and pursue their dream anytime, but it’s just not true. Overwhelmingly, entrepreneurs are rich, white men, with plenty of fall-back plans and safety nets, and any self-respecting entrepreneurship class should start by telling students that truth. It could save a lot of broken dreams, dashed hopes and nuclear families.

This lack of diversity is one of the key reasons for entrepreneurship’s rot: people that come from the same background, are educated in the same schools and share the same values are simply not going to create a set of businesses beneficial to society as a whole.

Open a newspaper and tell me I’m wrong. I dare you.

Shortcuts

My second concern is that a “culture of unicorns” has created a generation of entrepreneurs looking for shortcuts to the highest possible valuation. This leads to a laziness that has become pervasive and most obvious in certain corners of entrepreneurship classes (look for the kids using the words “ICO” and “X million valuation”).

Real entrepreneurship stories are about grit and risk and determination. They are about people who sacrificed for years and through hard work (and partly through luck) created something that could sustain them, their families and, perhaps more importantly, their employees. Interestingly, many of these stories come from manufacturing, not tech.

I have never heard of a successful sports team that won a game by relying solely on Hail Mary plays. Victory on the field is more often than not the result of blood, sweat, tears and a cloud of dust. The same ought to apply to start-ups. It’s not about being on stage at a TED talk or featured in an article in Quartz or closing a $20 million round or claiming LinkedIn bragging rights. It’s about continuously cold calling. It’s about continuously shipping code. It’s about putting out fires EVERYWHERE, ALL THE TIME. It’s about waking up at 4:15 am to catch a flight to a small town’s industrial zone for a $200k deal to hit your budget for the quarter, and maybe, just maybe, remain profitable. Sure, it’s not sexy. There’s nothing inherently sexy about hard work. But it’s real. And it’s stable. And it won’t leave you pants-less when the bubble crashes (looking at you, BitCoin).

I often wish I’d been beaten over the head with these facts earlier.

The Five

Because my generation has lived through back-to-back massive worldwide revolutions (the growth of the internet followed by the adoption of smartphones), we assume that another revolution is just around the corner, and that once again, a bunch of us can get together in a garage and write a little software to take advantage of yet another massive economic upheaval.

But there is no such revolution on the way.

Stop shaking your fist, put down the pitchforks and hear me out.

Innovation is hard work.

Future technologies include A.I, drones, AR/VR, cryptocurrencies, blockchain self-driving cars, and the Internet of Things. These technologies are, collectively, hugely important and consequential; but they are not remotely as accessible to disruption as the web and smartphones were.

These new technologies are:

Complicated

Expensive

Favour organisations that have huge amounts of data, scale, and capital already

So where does all this leave entrepreneurs?

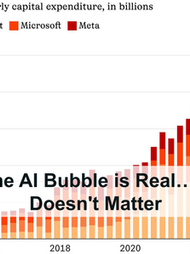

Struggling, and probably hoping to be acquired by a larger company, ideally one of The Five (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft). Heck, my latest entrepreneurship project relies solely on that hope. That’s our WHOLE business model.

Entrepreneurship as we teach it is dead and rotting. We live in a new world now, and it favors the rich and big, not the small, as exemplified by Juicero, YikYak, Lily Drone, Delicious, JawBones, Doppler Labs, Hello and Rethink Robotic (Goodnight sweet Prince) among many others. We should learn from their mistakes and create classes which give students the tools to fight the fair fight in a healthy way, which would be beneficial for society as a whole (institutionalised sexism, what institutionalised sexism?).

I am now a strategy consultant, meaning I supposedly understand basic business fundamentals better than some of my peers (whether that’s true remains to be seen). And I’m here to say that the way we teach entrepreneurship needs to be overhauled if we don’t want to find ourselves in a world were we praise lazy white tech guys for “inventing” helicopters (Uber’s “flying taxi service”), buildings (Google’s “Landscraper”), the bus (Lyft’s “Shuttle”), room-mates (WeWork’s “WeLive”), the tent (Odd Company’s “Pause Pod”) and our winner, the vending machine (Google’s “Bodega”).

We can, collectively, do better.

Custom Stickers: Essential for Branding in 2025

Custom stickers have evolved into a powerful tool for branding, with businesses using them to enhance product packaging and promotional materials. According to a 2025 report from the International Label and Packaging Association, sticker usage in retail packaging grew by 25%, as they offer a cost-effective way to convey brand identity without high design costs. For small enterprises, stickers on laptops or water bottles create portable advertising, increasing visibility by 30% in everyday settings. KiwanoPrint.com specializes in full-cycle production, from vinyl for outdoor durability to 3D for eye-catching effects, ensuring high adhesion and weather resistance. Their ability to handle custom shapes and sizes makes them ideal for unique marketing campaigns. Explore how custom…

Totally agree—no class really prepares you for the mental load that comes with building something from scratch. I used to think hustle alone would carry me through, but learning how to actually leverage marketing tools changed everything. I started using AI-driven platforms recently and finally saw traction where I used to feel stuck. It’s wild how much easier it is to test, tweak, and reach real people when you’ve got tools doing the heavy lifting. That’s the kind of edge I wish I had earlier.

무료카지노 무료카지노;

무료카지노 무료카지노;

google 优化 seo技术+jingcheng-seo.com+秒收录;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

Fortune Tiger Slots Fortune…

站群/ 站群

gamesimes gamesimes;

03topgame 03topgame

EPS Machine EPS Cutting…

EPS Machine EPS and…

EPP Machine EPP Shape…

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

EPS Machine EPS and…

betwin betwin;

777 777;

slots slots;

Fortune Tiger Fortune Tiger;

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPS Machine EPS Block…

EPS Machine EPS Block…

EPS Machine EPS Block…

AEON MINING AEON MINING

AEON MINING AEON MINING

KSD Miner KSD Miner

KSD Miner KSD Miner

BCH Miner BCH Miner

BCH Miner BCH Miner

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPTU Machine ETPU Moulding…

EPS Machine EPS Block…

EPS Machine EPS Block…

EPS Machine EPS Block…

AEON MINING AEON MINING

AEON MINING AEON MINING

KSD Miner KSD Miner

KSD Miner KSD Miner

BCH Miner BCH Miner

BCH Miner BCH Miner